I am going to do my best to not make this a flame Bob Bradley blog. I will try to be reasonable and objective. My biggest concern with the USMNT is the lack of a philosophy, identity, or style that is uniquely our own and captures the essence of our nation. When you think of Brazilian soccer you think of the joga bonito, Spain has their tika-taka, the Dutch invented Total Football, Italy sits back and defends until you make a mistake and then they pounce, Germany is committed to its shape and moves as a cohesive unit, Argentina has their flowing passes and superb individual dribbling, etc., etc.

The United States is still very young in terms of soccer, we didn't really get started until sometime around the '90 or '94 World Cups, so we only have had about 15-20 years of history in the sport. Nevertheless, over that time the hallmark of the National Team has been industry and, to a lesser degree, athleticism. United States players work hard, have good conditioning, can run the full 90 minutes, and leave it all out on the field. Are these admirable qualities and a good foundation for soccer? Yes, undoubtedly. Are they a team philosophy? Perhaps, but if that is the end all, be all of US Soccer, we will never become more than a mediocre World Cup team, and that isn't good enough.

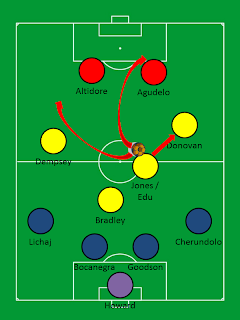

Bradley Ball, as many are wont to call it, is defined by this industry as well as an over-reliance on the completely unreliable long ball. We don't control the ball, opting instead to play a lot of long balls that are supposed to be directed to a holding striker. At least 6 of our current field players run first, defend second, and attack last (all 4 defenders and our two defensive holding mids). If any of them get into trouble, they boot the ball downfield, effectively ceding possession in order to maintain a sense of security in knowing that a the giveaway is occurring far from our own goal. These are effectively the same tactics that most of the intramural teams I played on in college use. That our national team plays the same style as a team composed of people who didn't even player soccer most of their lives is disconcerting, disappointing, and, at the end of the day, completely unacceptable.

If we want our soccer team to be an indication of who we are, and if I want to be entertained when I watch my national team, we need a change in how we play. Currently, the American version of the beautiful game is fairly ugly, mundane, and frustrating to watch. I don't ask that we win every game, I just ask that we put a product out there that I can relate with and that makes me want to watch and cheer.

The United States of America was not built on industrious labor alone, we don't just work hard, we are innovative and we work smart. This is the birthplace of the Industrial Revolution and the home of the internet. That dynamic is not there with our national team. Playing long balls is like picking the seeds out of cotton instead of using a cotton gin, or dusting off my old World Book Encyclopedia instead of using Google on my phone. It's less effective, simple, archaic, outdated, and won't get us where we want to be. In my opinion, we don't necessarily need Spain's tika-taka or Brazil's joga bonito, but we need incisive through-balls, we have to learn to control the midfield, to possess the ball, and to laugh in the face of defenders who think they can take it away from us. We need creative and smart runs off the ball. We run like mad when the other team has the ball and stand around like statues once we win it from them. That isn't smart soccer, and it isn't productive industry, it's wasting our energy just to boot the ball back to them and waste more. Anybody who has played football, basketball, or soccer knows that you expend way more energy playing defense than you do playing offense. Why? Because you should know where the ball is going on offense and you can take a direct path to where you need to be instead of reacting to what others are doing. We are wasting our industry in the least productive aspect of the game.

If US soccer is to take the next step and if we truly want to be counted among the world's elite teams, our tactics have to change. My primary criticism of Bob Bradley is his unwillingness to invest in a system that pays dividends greater than what we have seen in the past. I know we will suffer growing pains during the adjustment, I know results won't come immediately, but the adjustment has to be made if we don't want to be mired in mediocrity for the foreseeable future. America has never been satisfied with mediocrity, except, it seems, for the USSF.